Energy and How We Use It

Like gasoline in a car, food fuels our body and powers our ability to navigate the world. The energy we have for the day is our Total Daily Energy Expenditure (TDEE). TDEE is an estimate of how many calories (or kCals, but we like to keep it simple with "calories") our body uses in a day. It's split into different categories, or "energy bins," each representing a different way our body burns energy. Let’s break them down:

1. Basal Metabolic Rate (BMR)

This is the minimum energy your body needs to just function—basically, the energy to "keep the lights on." In other words, it's the calories required to do absolutely nothing except stay alive and awake. It also represents what people often refer to when they talk about metabolism, which can vary a lot from person to person.

2. Thermic Effect of Food (TEF)

TEF is the energy required to process the food we eat—basically, it’s the calories burned just by digesting, absorbing, and storing the nutrients from your food. It might seem odd at first, but it actually takes energy to turn food into usable energy.

3. Physical Activity (PA)

This is the energy burned during intentional movement—anything from doing the dishes to going for a jog, or even more intense activities like lifting weights or running sprints. It covers pretty much all forms of exercise or structured physical activity.

4. Non-Exercise Activity Thermogenesis (NEAT)

This is a tricky one! NEAT covers the energy you burn doing all the little activities throughout the day that aren't formal exercise—stuff like walking to the bathroom, fidgeting, or even talking. This is where most of our energy burns happen, but it's also the one that’s hardest to consciously control. For example, right now, I’m shaking my legs while writing this. That’s NEAT.

Putting It All Together: The TDEE Formula

TDEE = BMR + TEF + NEAT + PA

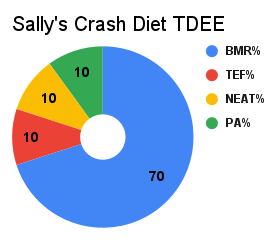

If we had to break it down as a percentage of how most people’s TDEE is divided up, it would look something like this:

Yes, you read that right—Physical Activity is often a smaller portion, even though most people focus on it the most when thinking about weight management. Now, here’s where things get interesting: If you decide to go all in on a tough workout, your body will often respond by dialing down NEAT, which means less fidgeting, less walking around, and fewer spontaneous movements throughout the day. So, if you're pushing yourself hard at the gym, you might not even realize you're subconsciously reducing your daily activity in other ways. Let’s dive into a couple of examples to see how this works.

Bob’s Manic Self-Flagellation

Bob is a reasonably fit guy who has been maintaining a decent body composition, but his office job has led to some unwanted weight gain. He starts hitting the gym harder to make a change. On Day 1, after work, he does a quick lift session and some cardio. On Day 2, feeling extra motivated after reading some David Goggins, he wakes up and runs several miles before hitting the gym for a heavy lifting session. Afterward, he feels like a total wreck at work, barely able to focus, and just generally wiped out.

Here’s the thing: It's very possible that Bob’s TDEE on Day 1 and Day 2 could be the same, even though Day 2 felt way more intense. That’s because on Day 2, Bob's body might have responded to the extra effort by reducing NEAT, meaning he was probably sitting still more at work, not fidgeting, and even avoiding any extra movement like talking to coworkers or taking the stairs.

Sally’s Wedding Preparation Woes

Sally’s a bridesmaid in an upcoming wedding, and for some reason, she’s convinced that she needs to lose 10 pounds to fit into a smaller size dress. (We'll put aside the whole body-image issue for now, but trust me, it's a problematic mindset). To lose the weight, she decides to go on a juice cleanse.

Before she starts, Sally’s TDEE is around 2,000 calories. But once she starts restricting her intake to around 1,000 calories a day, she enters a massive deficit. For the first month, she loses 5 pounds and feels pretty good about it. But by month two, the weight loss stops, and she’s feeling exhausted and struggling to keep up. Sally gives up on the cleanse, feeling like she failed. But here's the thing: her body has actually made some major adaptations to deal with the drastic restriction.

By the second month, Sally’s TDEE has dropped because her body has downregulated her BMR and almost completely eliminated NEAT. This means she’s no longer in as deep of a calorie deficit as she thought, has no energy for workouts, and the weight loss has stalled. She’s also likely lost muscle mass along with fat, and this approach, as extreme as it is, can easily lead to disordered eating patterns.

Blake’s Dreamer Bulk (Yep, That’s Me)

Now let’s switch gears and look at what happens when you go in the opposite direction: trying to bulk up with a massive caloric surplus. I’ve always been on the smaller side and after my initial "newbie gains," I decided I needed a bigger surplus to gain muscle faster. So, I thought, “Why not bump up my calories to 4,500 a day?” Even though my maintenance calories were around 3,500, I figured I needed a huge surplus to maximize muscle growth. Where optimal muscle growth potential occurs (OMGP) with an addition of 200-300 surplus calories. Alas, this was my “Dreamer Bulk” era.

For a while, things seemed great. My lifts were going up, and I saw some muscle growth. But after about two months, I started noticing some not-so-fun side effects. My blood lipids were out of whack, and I even started wheezing—at basketball and while in the bedroom... well, let's not get into the details.

After four months, I had gained a fair bit of muscle, but I also packed on more fat than I intended. Where were all hyper surlus calories to go anyway? So, I went into a cut, trying to lose the excess fat slowly, at about 1-2 pounds per week. The end result? I gained the same amount of muscle as I did on my last bulk, and the whole process took way longer.

Moral of the story?

Sometimes, more calories don’t equal more muscle—at least not without the negative consequences. A more measured approach is key.

Conclusion

TDEE is a super useful model for understanding how our body uses energy and how the different bins (BMR, TEF, NEAT, PA) interact with each other. It can also help us take a step back and avoid making drastic decisions based on the feeling of urgency we often get around fitness and nutrition. Extreme approaches can lead to robbing Peter to pay Paul—whether it’s dialing down NEAT to up PA, or dramatically restricting calories to try and speed up fat loss.

The bottom line: The body is amazing at adapting, but in a world where food is abundant and we’re increasingly sedentary, understanding these mechanisms is more important than ever. Now that we know what’s going on with TDEE, we can make smarter, healthier decisions that lead to better, more sustainable results.